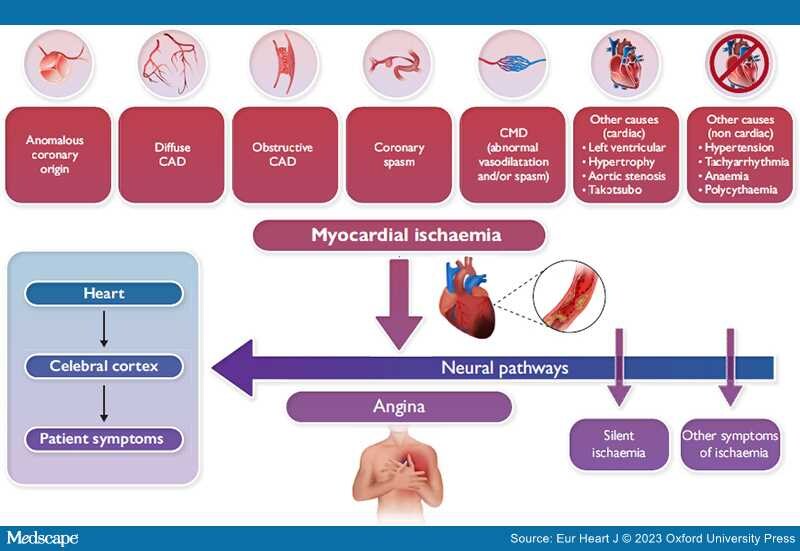

Graphical Abstract

Many mechanisms may cause myocardial ischaemia other than epicardial coronary artery obstruction. CAD, coronary artery disease; CMD, coronary microvascular dysfunction.

'But there is a disorder of the breast marked with strong and peculiar symptoms, considerable for the kind of danger belonging to it, and not extremely rare, which deserves to be mentioned more at length. The seat of it and the sense of strangling and anxiety with which it is attended, may make it not improperly be called angina pectoris. Those who are afflicted with it, are seized while they are walking (more especially if it be uphill, and soon after eating) with a painful and most disagreeable sensation in the breast, which seems as if it would extinguish life if it were to increase or to continue; but the moment they stand still, all this uneasiness vanishes. In all other respects, the patients are, at the beginning of this disorder, perfectly well, and in particular have no shortness of breath, from which it is totally different. It likewise very frequently extends from the breast to the middle of the left arm'.

—Heberden (1772). [1]

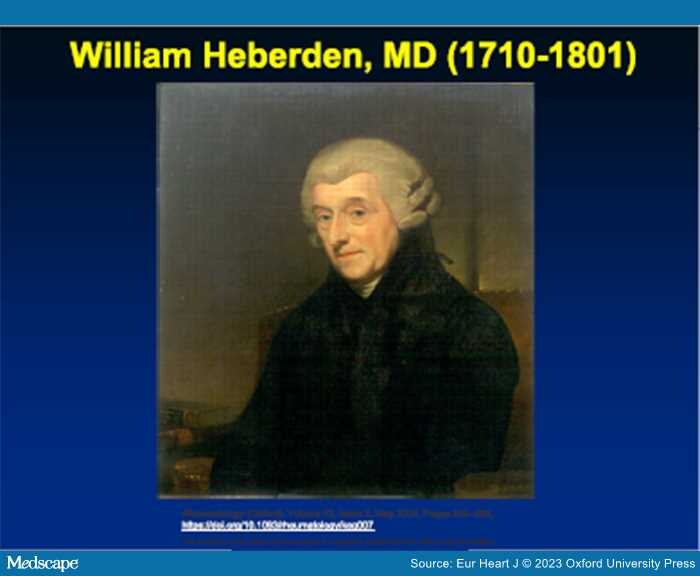

In 1772, 4 years after his initial description of angina pectoris, William Heberden (Figure 1) published his seminal account of this clinical disorder,[1] which remarkably has stood the test of time despite profound developments in the diagnosis and management of ischaemic heart disease, particularly during the last half-century. Angina pectoris is widely regarded as the cardinal symptom of coronary artery disease (CAD), though frequently this term has become synonymous with 'chest pain'. It is instructive that the term angina derives from the Latin word 'angere' ('to strangle') and from the ancient Greek word 'ἀγχóνη' ('anguish'). Presumably Heberden chose the term angina to convey the ominous sense of impending doom and torment from a disorder he characterized as a 'most disagreeable sensation in the breast, which seems as if it would extinguish life if it were to increase or continue'.[1] Had Heberden instead been trying to simply convey the symptom of chest pain, he would likely have used the Latin term 'dolor pectoris'.

Figure 1.

Portrait of William Heberden, MD.

Heberden's description of angina teaches us also the importance of eliciting a careful clinical history; indeed, querying patients with suspected CAD by using the more restrictive term 'chest pain' may lead some to deny this as a true description of their presenting symptoms. Thus, in probing suspected myocardial ischaemia, it may be preferable to pose various descriptions of anginal symptoms to patients (e.g. 'do you have chest discomfort, pressure, tightness, heaviness, a squeezing sensation, or mid-epigastric burning, etc.?' ). Presumably this would increase the likelihood of capturing the panoply of potential clinical expressions of angina.

Beyond merely describing symptoms, Heberden also raised the possibility that 'spasm of the heart' could be the mechanism responsible for angina, and subsequently others in the 1800s also hypothesized that spasms of the coronary vessels were responsible for the condition. Subsequently, in 1903, Colbeck[2] entertained the concept of 'pseudo-angina' or 'angina cordis vasomotoria' as he termed it—perhaps the first true description of vasospastic angina prior to the scholarly work of Myron Prinzmetal, who is largely credited with this observation in 1959,[3] while Maseri and coworkers[4] and Yasue et al.[5] likewise called attention to vasospasm in the 1970s and 1980s.[4]

Studies performed at the end of the past century to clarify the origin of ischaemic symptoms demonstrated that angina is caused by accumulation of various chemical substances within ischaemic myocardium, mainly adenosine, which stimulate pain receptors. The neural signalling pathways involved in ischaemia are inherently complex and are modulated in intrinsic cardiac, mediastinal, and thoracic ganglia which, in turn, are propagated to the cerebral cortex where they are decoded as angina (Graphical Abstract). There is large individual variability as to how ischaemia is perceived and a sizeable proportion of ischaemic episodes are not associated with angina;[6,7] thus, ischaemia may be 'silent' in a certain proportion of individuals, possibly depending on alterations in neural pain processing mechanisms.[6] 'Silent myocardial ischaemia' is thought to occur more commonly in patients with diabetes who have autonomic neuropathy and altered pain perception.[6,8] Of note, accounts of asymptomatic ischaemia ('angina sine dolore'/'angina without pain') likewise date back to the early 1900s.[2] While silent or asymptomatic myocardial ischaemia may occur in 10%–20% of stable CAD patients, the absence of anginal symptoms should not be considered synonymous with low cardiovascular risk.[9]

Furthermore, it is increasingly commonplace today to cite symptoms other than angina, including dyspnoea and excessive fatigue, as 'angina equivalents', though Heberden explicitly disregarded this in his original description of angina, wherein he states: '…and in particular, [they] have no shortness of breath, from which it [angina] is totally different'. While dyspnoea may coexist with angina, the diagnostic specificity of dyspnoea alone is much less clear. The recent European chronic coronary syndrome guidelines show that dyspnoea alone has a pre-test probability for obstructive CAD ranging from 20% to 32% in middle-aged men and only 9%–14% in women.[10] Also, given the nonspecificity of dyspnoea, which can frequently occur in many other conditions including obstructive lung disease, obesity, anxiety, and in sedentary individuals with physical de-conditioning, isolated dyspnoea in the absence of chest discomfort should not be viewed invariably as an 'angina equivalent'. Thus, it would be more appropriate—in the absence of chest discomfort—to classify such subjective findings as 'other symptoms due to myocardial ischaemia'.

Yet, we must recognize that symptoms can be associated with the disease endotype. For example, both chest pain and dyspnoea may occur in the presence of extensive ischaemia. Walk-through angina is a phenomenon observed in patients with chronic CAD whereby angina symptoms improve despite the continuation of the effort, probably resulting from local vasodilatation and recruitment from donor connections. Importantly, the presence of angina does not inform us as to the precise causes and mechanisms of ischaemia. Moreover, the association and presumed pathogenetic link between angina pectoris and obstructive CAD have also led to unidimensional thinking and a failure to consider other important causes of ischaemia. The persistent view that obstructive CAD is the most common cause of angina pectoris likely finds its origins with the advent of selective coronary angiography by Sones in 1959 and the ability to visualize epicardial coronary stenoses. In the decades thereafter, the widespread adoption of invasive coronary angiography has often led to an invasive approach to angina management predicated on defining (and treating) epicardial coronary obstructions with stents or bypass surgery. For this reason, it has become virtually axiomatic that obstructive CAD is the sine qua non of angina pectoris and myocardial ischaemia. And, as noninvasive diagnostic approaches such as coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) have become increasingly utilized clinically and are often now embedded in healthcare systems that prioritize virtual or remote telephonic consultations and triage by nonmedical healthcare professionals, the algorithmic focus on detecting anatomic obstructive CAD has shifted demonstrably to the first-line use of anatomical CCTA rather than functional testing, thus further reinforcing a singular management approach that may be agnostic to important nonanatomic causes of angina and ischaemia.

It is also abundantly clear that angina has various clinical presentations, including rest or exercise-induced angina, with a fixed or variable threshold, that can be caused by a variety of structural and functional mechanisms affecting coronary blood flow or vasomotor tone, including both epicardial coronary and microvascular spasm, as well as derangements of myocardial metabolism.[4,10–13] We must also recognize that because functional mechanisms may coexist with obstructive CAD, these precipitants of angina and ischaemia are not necessarily mutually exclusive and can often coexist in the same patient.[10–13] In support of this perspective, a previous, large observational study of almost 400 000 angina patients who underwent elective coronary angiography found that among those with a positive noninvasive stress test, only 41% had obstructive CAD.[14] Similarly, the pre-test probability of obstructive CAD in middle-aged men (age 50–69 years) ranges from just 32% to 44%.[10] Thus, while only a minority of patients with angina have obstructive epicardial CAD, nonobstructive causes, by contrast, are more common yet much less well-appreciated diagnostically and therapeutically.

Finally, there are also potentially detrimental consequences of either not considering the multiple mechanisms of stable myocardial ischaemia or missing a diagnosis of angina caused by functional alterations of coronary circulation. First, patients with true angina pectoris but without epicardial stenoses may be dismissed without a diagnosis, either when cardiologists shift their attention to probing noncardiac causes of chest discomfort or possibly refer the patient to other specialties. Second, angina patients with nonobstructive CAD frequently have a compromised quality of life which may be further limited by invalidating symptoms. Third, some patients may be exposed to the risk of myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death, particularly those with epicardial coronary spasm that is not treated effectively. Fourth, the cost to the healthcare system is considerable as rates of recurrent hospitalizations and repeat coronary angiography are appreciable, especially for patients with microvascular angina. Nevertheless, we must likewise acknowledge that there are also notable nonatherosclerotic causes of chest discomfort that should be considered in addition to coronary and noncoronary causes of angina, including aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension, and after Takotsubo syndrome, among others.

In summary, the paradigm that obstructive CAD is synonymous with angina pectoris and myocardial ischaemia needs to be reconsidered because it is not universally applicable to the larger, more unselected universe of individuals presenting with stable angina in whom flow-limiting coronary stenoses are often not present.[4,10–13] Perhaps this 250th anniversary of Heberden's original description of angina may represent an opportunity to reprise this syndrome with a renewed recognition that the clinical manifestations of ischaemia are protean and that nonobstructive causes are both common, yet remain under-appreciated. We must also recognize that knowledge of the precise mechanism of ischaemia due either to epicardial coronary stenoses or nonobstructive causes may lead to more personalized anti-anginal treatment, which offers the hope of substantially improving symptoms and quality of life in a broader population of patients with 'Heberden's angina' in the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

The authors dedicate this paper to the memory of Professor Attilio Maseri (1935–2021), who educated and inspired generations of cardiologists with his pioneering work dedicated to elucidating the pathophysiology and mechanisms of angina pectoris, most notably on vasomotor function. Dr Maseri held academic university appointments at University of Pisa; Royal Postgraduate School at Hammersmith Hospital, London; Catholic University Sacro Cuore of Gemelli Hospital, Rome; and Vita-Salute University of San Raffaele, Milan.

Funding

There was no external funding associated with the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

Eur Heart J. 2023;44(19):1684-1686. © 2023 Oxford University Press

Copyright 2007 European Society of Cardiology. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.