CORRECTED November 14, 2022 // An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of Lev Spivak-Birndorf. It has since been corrected.

I was in the exam room, saving my big question for last, as one does.

It was my first meeting with my new GP in Colorado, and I was impressed with his fluid citations and advice from recent studies on heart disease, exercise injuries, and musculoskeletal pain–three of my major sore points.

So far, so good.

Then I ventured my last question. "I've been having sleep difficulties ever since my older son was born." (Note: That was during the first Bush administration.) "But now that I'm in Colorado, I wonder if cannabis might help me through the night? I hear it's good for that."

Suddenly, my doctor clammed up.

"I've heard some things, too," he told me. "But I can't advise you on that, because I could lose my license." He could no more recommend cannabis than he could heroin or ecstasy — because all are designated Schedule 1 drugs on the federal level. (Though that could change, given President Joe Biden's recent moves toward marijuana reform.)

So now I had a choice: I could "just say no to drugs," as Nancy Reagan encouraged me to do. Or I could begin experimenting. As a health journalist for two decades, I know anecdotal evidence is often no more than wishful thinking. And yet, my standards slip when I stare at the ceiling at 3 a.m., and dawn is a long way off.

In an age of red-versus-blue discord, cannabis is one of the few arguably purple issues. Thirty-seven states, DC, and three territories — including such conservative hotbeds as Oklahoma and Alabama — have passed comprehensive medical marijuana laws, permitting treatment for 42 conditions. Twenty-one states, DC, and two territories allow adults to use it for whatever reason, from pain relief to partying. Which leaves only Kansas, Nebraska, and Idaho standing with federal lawmakers from 1970, in agreeing that cannabis is just as addictive and dangerous as heroin, cocaine, LSD, and ecstasy.

Dr Erik Smith

"Most physicians are not trained in cannabinoid medicine," says Erik Smith, MD, a Philadelphia doctor and physician partner with Veriheal, a healthcare technology company that provides personalized cannabis education to patients. "And they're under a lot of pressure from the healthcare system, because cannabis is a Schedule I drug. So patients have to go by word of mouth, outside the realm of medicine."

When I was an editor at a health magazine, the surest way to kill any story idea was to dismiss it as being based on mere "anecdotal evidence," which we regarded as a synonym for "fairy dust" or "snake oil."

No double-blind study, no deal.

Smith didn't have that luxury. He took his training in obstetrics and gynecology. And when his pregnant patients came to him with refractory nausea and vomiting, he went off the books, and told them, "I know somebody who can help you."

Right: a cannabis dealer.

And while you register shock that an M.D. would recommend an extra-pharmaceutical treatment, consider this: Opioids are an approved drug, and they killed 68,630 people via overdoses in 2020 alone, according to the CDC. Deaths by cannabis overdose are either nonexistent or exceedingly rare.

That was part of Smith's calculation, when he took over a roster of patients who were (a) pregnant, and (b) self-medicating with opioids and other drugs, to the point of addiction.

"Nobody wanted to touch these patients," he says. "We started with addiction specialists and began working with the synergistic effects of cannabis to help our patients go off opioids. There were better outcomes, and they were able to deliver their babies."

The Politics of Pot

Smith wasn't the only one listening to patients' experiences with cannabis. After California approved medical marijuana in 1996, momentum began to build. The movement went national in 2013, when Sanjay Gupta, MD, on CNN, told the story of Charlotte Figi, a five-year old Colorado girl with Dravet Syndrome, a form of epilepsy. She was suffering 300 grand mal seizures a week, until her staunchly anti-drug parents heard about a California boy whose seizures were stopped by a cannabis strain high in cannabidiol, or CBD.

In desperation, they worked with a cannabis producer in Colorado Springs to grow a high-CBD strain that would be called Charlotte's Web. Her seizures stopped, and a DIY movement was born, often among people who, like the Figis, were surprised to turn to a notorious drug for help and healing. (Sadly, Charlotte died in 2020, likely due to Covid.)

Dr G. Malik Burnett

G. Malik Burnett, MD, is an addiction medicine specialist in Baltimore, and co-author of a study called "Policy Ahead of the Science: Medical Cannabis Laws Versus Scientific Evidence." That sums up the problem with cannabis therapies today: The treatment cat is out of the medical-research bag, and running all over the 42-odd conditions that justify a medical marijuana card — and a hundred others that do not.

As Burnett's study says: "US medical cannabis laws are in conflict with federal law and often with science as well."

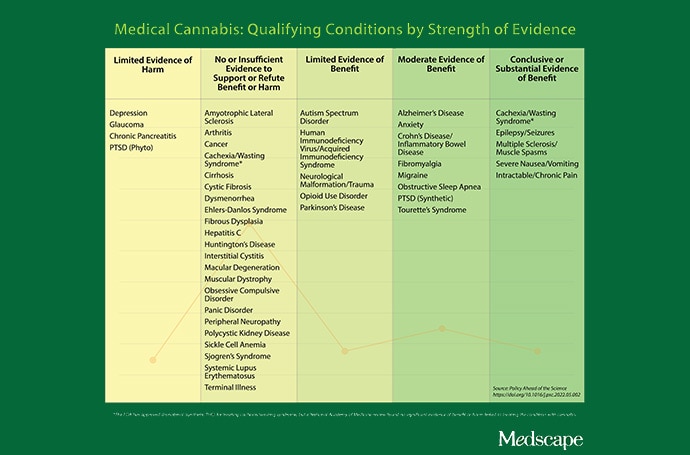

And yet, Burnett is far from a cannabis naysayer. In his study, he notes that the most commonly included conditions on state lists — cachexia/weight loss, muscle spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis, nausea and vomiting, chronic pain, and seizures — are also the ones with the most evidence that cannabis therapy works. But the lists also stray into areas where there is no evidence (ALS, arthritis, cancer), limited evidence (autism, HIV/AIDS, opioid-use disorder), or even evidence of potential harm (glaucoma, depression, PTSD).

Burnett recently testified before Congress in support of decriminalizing cannabis at the national level. His reasoning: to address the prejudicial way drug laws have been applied against people of color, and to help clear the 100-year logjam against medical studies of marijuana. Only then will the evidence sort itself out into what works and what doesn't.

Cannabis was common in patent medicines in the early 1900s, but as the plant began to travel north with immigrant workers from Mexico, U.S. officials woke up to the "threat." With mounting hysteria, they passed increasingly draconian laws to prohibit cannabis use for anything at all, including better health. The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, passed over the protests of the American Medical Association, began the demonization process. (Regulators insisted on calling it "marihuana," in fact, to emphasize that foreign people were using it, and that it was suspect for that reason.)

Charlotte's dramatic tale led to lots of personal testimony before state legislatures, by people whose stories were hard to ignore: veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, parents of kids with epilepsy, people with AIDS, chronic pain sufferers, and people recovering from drug addiction. All of these, and more, were flouting federal law by using cannabis to treat their afflictions. Clinical trials were unavailable because cannabis research was illegal, too. But word of mouth proved powerful, and legalization took off at the state level.

The Healing History of Cannabis

For all the federal chest-pounding against cannabis, there's a certain irony there, too. The first U.S. patent for cannabis-as-medicine is held by none other than the Department of Health and Human Services. They applied for the patent in 1999 for cannabinoids to be used as anti-inflammatories and neuroprotectants. Something was in the air, and not just at Grateful Dead revivals.

The high-producing ingredient in cannabis — delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC — was first isolated in 1964, by Israeli researcher Raphael Mechoulam and his team at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who were free to chase their research wherever it might lead. (Israel remains the world leader in cannabis research, says Smith.) Twenty years later, they discovered that the human body has a multitude of cannabinoid receptors in the brain, gut, skin, immune system, organs, and reproductive system.

A study in Cerebrum called it "literally a bridge between body and mind." These receptors are activated by endogenous cannabinoids. That is: cannabinoids produced by the body's own internal dispensary. Soon the endocannabinoid system, or ECS, took its place alongside the circulatory system, nervous system, immune system, and endocrine system, as a primary body regulator.

"It led researchers to look at the endocannabinoid system for lots of additional therapeutic possibilities," says Burnett. And suddenly exogenous cannabinoids — from the cannabis sativa plant — were gaining credibility as healing agents as well, first from the self-medicating public, but also from scientists. The latter were very late to the game: Cannabis had been cultivated for health reasons for 11,000 years, according to archaeological discoveries in China and elsewhere. Even Queen Victoria signed on; her personal doctor prescribed cannabis tinctures to help soothe her painful menstrual cycles.

Burnett wasn't willing to take her word for it, of course. In "Policy Ahead of the Science," he and two collaborators gathered the evidence — still less than definitive, but growing — of cannabis's effectiveness for all 42 conditions. Among them: multiple sclerosis, cancer, ALS, HIV/AIDS, Crohn's disease, and epilepsy.

If those maladies seem all over the place, it's because the ECS is all over the body, as well.

Users Ahead of the Research

Lev Spivak-Birndorf, 40, didn't need to be told that cannabis is effective in treating Crohn's. He discovered it all by himself. Growing up in Michigan, he began experiencing cramping, abdominal distress, and appetite challenges when he was 15. "I was diagnosed with Crohn's, and they prescribed prednisone as an anti-inflammatory," he says. "Any improvement felt amazing."

But he was also experimenting with cannabis at this time, as teens will do. (Note: There is some evidence that cannabis may harm developing brains.) Spivak-Birndorf noticed a correlation between his cannabis use and a lessening of his symptoms. Now he treats his condition with indica strains (said to be sedating, compared with sativa strains, which are thought to be more invigorating), taking prophylactic doses, say, before a Thanksgiving meal that might rile his digestive tract.

"I'm not a medical doctor. I can't say that cannabis has cured me," he says. "But I will say that, after my last couple of colonoscopies, my doctors have told me that I really don't have Crohn's anymore."

Based on this experience, and his education as a geochemist, Spivak-Birndorf eventually gravitated to the cannabis industry, as chief science officer for PSI Labs, a cannabis testing facility in Michigan. "The fun part of being in this industry is watching products evolve and making them safer."

Adam Young knows something about devoting a career to cannabis. He works at Realm of Caring, a Colorado-based nonprofit that was launched by Charlotte Figi's mom, Paige. Their volunteers have counseled 75,000 people worldwide on how to implement cannabinoid healing protocols, basing their advice on the experiences of other users, 800 peer-reviewed articles, and training in regulations and medical-cannabis history. Young and his associates have also created a giant database of patient reactions to various cannabis regimens, which is "anecdotal evidence" writ large. They also publish scientific studies based on that data.

Young gained valuable experience with cannabis protocols in 2012, when his mother was suffering from multiple myeloma cancer.

"She was down to 65 pounds" from her radiation and chemotherapy treatments, says Young, "so I packed up all my stuff and moved to be with her."

His mother was expected to live for just five more months, and the treatments were debilitating. So Young and his mother decided to "try something new." Young researched protocols for people suffering from wasting syndrome, which afflicted many AIDS patients during that pandemic. Through his connections in the cannabis community, where he counseled non-violent drug offenders, he found a concentrated form of cannabis oil that might help his mom. Her doctors backed off from the unfamiliar therapy, telling them: "We can't work with you."

But they persevered. "In only two months, there was a reversal of what I had seen. She was back up to 95 pounds," Young says. "I had my mom back."

Experimenting With Cannabis: Finding the Right Plan for You

So what about me and my health issues? I really did want to talk to a doctor, so I turned to Veriheal (the cannabis-education company Smith consults for).

For $110, Veriheal will arrange a telehealth consultation with a medical professional. In my case, it was Carlie Bell, ND. She's a naturopathic physician in Houston, having completed undergraduate studies in pre-med, plus a four-year graduate program in therapies that help the body heal itself. Bell is also a cannabis educator at Saint Louis University, working with practitioners who want to give better answers than my GP did.

She crackled to life on my computer via a telehealth app, and soon we were deep in the weeds of my sleep issues. Bell listened to my sleeplessness woes, cited research on the ECS, and recommended that I commence a protocol using full-spectrum CBD (meaning it's derived from whole-flower cannabis). She proposed that I take it in tincture form, two hours before bedtime, and hold it under my tongue for 45 seconds to a minute. The benefits: The CBD would be absorbed through mucous membranes in my mouth, for an immediate calming effect, but the amount that I swallowed would work its way through my digestive tract, for a longer-lasting soporific effect.

I experimented based on the advice and found a plan that worked for me: I start the night with a prescription to help with my restless legs syndrome, then use a sublingual cannabis if I am wakeful in the middle of the night. It hasn't cured my insomnia, but it has given me treatment options I didn't have before. I awake refreshed, with no grogginess — a common problem I had when I was taking prescription sleeping pills.

Bell reiterated cautions I was to hear half a dozen times, as I completed research for this story:

Start low, go slow. When experimenting with psychoactive forms of cannabis —those with THC — take a minimum dose several days in a row, before titrating up until you receive the desired effect. CBD won't make you high, but you should be wary of dosing there, as well. Taking too many cannabinoids may cause arousal, not sleep.

Choose preparations that are easy to measure, use, and adjust as needed. A calibrated eyedropper can help you dial in a dose, a cannabis cookie not so much. A vape pen allows you to start with one inhalation, see how you feel, and move up (two puffs) or down (a shallower puff).

Beware of edibles. Just like candy, right? Yes, but with a crucial difference. It can take up to two hours for a THC edible to take effect, which leads some to double dose while waiting for the first one to kick in. That kind of double whammy can lead to a miserable 12 hours of feeling "too high," and only time can relieve it.

Quality counts. Compare makers. Some apply rigorous standards to their cannabis products, including making sure that doses are uniform, and that they're uncontaminated by pesticides or toxins. Unscrupulous formulators let it slide. You need to know the difference.

Take a deep dive into studies about treating your particular condition with cannabis. You can start with the chart above from "Policy Ahead of the Science," which will give you an up-to-date idea of how strong, or weak, the evidence is that you can gain help from cannabis. Realmofcaring.org also has an online research library, and condition-specific websites (sleepfoundation.org, for instance) can guide you as well. Use Reddit and chat groups at your own risk.

Consult your doctor and pharmacist. As legalization spreads, so does training among healthcare providers. If your physician can't speak knowledgeably (or at all) on the subject, you may want to supplement their advice through Realm of Caring, Veriheal, or a local physician who specializes in natural remedies. Pharmacists will know if cannabis might clash with other medications. (In Pennsylvania, every dispensary is required to have a pharmacist on staff.) The budtender in a dispensary can help with suggestions based on personal experience, as well. But it's kind of like asking your 13-year-old for computer advice: Results may vary.

Sources:

Erik Smith, MD, cannabinoid medicine physician in Philadelphia

G. Malik Burnett, MD, addiction medicine specialist in Baltimore

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. "Drug Scheduling." https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling (Accessed November 2022)

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022). "State Medical Cannabis Laws." https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). "The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research." https://doi.org/10.17226/24625

CNN. (2013). "Marijuana Stops Child's Severe Seizures." https://www.cnn.com/2013/08/07/health/charlotte-child-medical-marijuana

Psychiatric Clinics of North America. (2022). "Policy Ahead of the Science: Medical Cannabis Laws Versus Scientific Evidence." https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2022.05.002

Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. (2020). "History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system." https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.3/mcrocq

Cerebrum. (2013). "Getting high on the endocannabinoid system." https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3997295/

U.S. Department of Justice and Library of Congress. (2018) "Is Cannabis a Gateway Drug? Key Findings and Literature Review." https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/252950.pdf

Office of National Drug Policy and the Rand Corporation. (2013). "Improving the Measurement of Drug-Related Crime." https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/drug_crime_report_final.pdf

The Lancet. (2019). "The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): a multicentre case-control study." https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30048-3

Reason Foundation. (2018). "Does Recreational Marijuana Legalization Contribute to Homelessness?" https://reason.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/homelessness-effect-of-marijuana.pdf

Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment. (2020). "THC Concentration in Colorado Marijuana: Health Effects and Public Health Concerns." https://www.thenmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/THC-Concentration-in-Colorado-Marijuana-_CDPHE-8.3.2020.pdf

Cato Institute. (2021). "The Effect of State Marijuana Legalizations: 2021 Update." https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/effect-state-marijuana-legalizations-2021-update

Credit:

Lead image: Dreamstime

Image 1: Veriheal

Image 2: Dr G. Malik Burnett

Medical Cannibis Graphic: Medscape

WebMD Health News © 2022

Cite this: What's Medical About Marijuana? - Medscape - Nov 10, 2022.

Comments