This discussion was recorded on July 21, 2022. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I'm Dr Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Today we have a distinguished panel joining us to discuss their important research for rapidly identifying patients with compromised lung function — particularly from COVID-19 — who may be at risk for hypoxia and therefore require not only supplemental oxygen but also potentially a higher level of care.

Joining us to discuss their important research is Dr John B. West, emeritus professor of medicine and physiology, UC San Diego School of Medicine (UCSD), who's authored more than 500 articles and the well-known textbook Respiratory Physiology: The Essentials. Also joining us is Dr [William] Cameron McGuire, pulmonary–critical care physician and clinical instructor at UCSD.

Welcome to both of you, gentlemen.

John B. West, MD, PhD: Thank you.

William C. McGuire, MD, MPH: Thanks for having us.

Glatter: Dr West, I'd like to start with you. Triaging patients, we've traditionally used pulse oximetry. It's quick and easy, but there are problems with it. One problem is that skin type can affect how we measure oxygenation, and because of this, it can overestimate the need for oxygen. Especially among patients with COVID-19, we experience this phenomenon. Please explain the new concept that you've developed in your research, known as the oxygen deficit, and then talk about pulse oximetry and how it compares.

West: I agree with you that the pulse oximeter is a tremendous innovation. There's no question that it's extremely valuable in the triage of patients with COVID-19, for example. The alveolar gas meter (AGM) that we've developed is something that gives us more information. It uses the pulse oximeter, but in addition, it looks at the expired gas of the subject. The subject just breathes though a valve box, which is very easy to do. We compare the oxygen in the air in the lung with the pulse oximetry measurement, and that gives us much more information.

Pulse oximetry gives you a single number of the level of oxygen in the arterial blood, and that's very valuable, but it's even better to be able to look at the differences between what's happening in the lung and what's happening in the blood. That is what the AGM device can do, and it works very well. It's very efficient.

It's not a problem for the patient at all. The measurements can be done in a couple of minutes or so. It's an advance in determining the overall gas exchange picture of the lung, which is important in COVID-19, because that particular virus — for some reasons that I don't understand — seems to particularly attack the gas exchange portions of the lung (the alveoli), and hypoxemia is very much a feature of it.

Glatter: In terms of respiratory failure, we are always concerned about type 1 respiratory failure, but type 2 with hypercarbia would be a concern, and we might be missing patients who have a saturation of 92%-93% or lower, and they may also be hypercarbic. With your device, I would assume that with this oxygen deficit, it would be able to pick up this impaired gas exchange. Is that correct?

West: Absolutely correct. One of the readouts is the alveolar PCO2. You can see immediately just by looking at the screen what the PCO2 is, and if it's abnormally high, that is obvious. That is certainly one of the values of the instrument.

Glatter: Dr McGuire, I'd like to bring you into the discussion and have you talk about the device. Could you demonstrate the device, talk about values it derives, how this compares in normal vs diseased tissue, and maybe talk about COVID-19 a bit?

McGuire: I'm going to turn my camera here so that everyone can see the device. This is the AGM. I'm starting it from the very beginning. I'm going to log in, which takes about 5 seconds. Once the machine tells you, the practitioner, that you are ready to measure, it goes on to another screen, at which point you instruct the patient to breathe through a mouthpiece with a nose clip in place (as I'm going to do) and place a pulse oximeter on the finger. I'm going to stop speaking for about 30 seconds and get a measurement.

I'm going to stop data acquisition there, even though the machine is not quite at steady state, and then we'll readjust the camera in a moment to talk about the values. Essentially, what I just did was what I asked patients to do in the study: Breathe normally — tidal breathing, as if they were ignoring my presence in the room, as if they were reading a newspaper or watching TV, is how I instructed them.

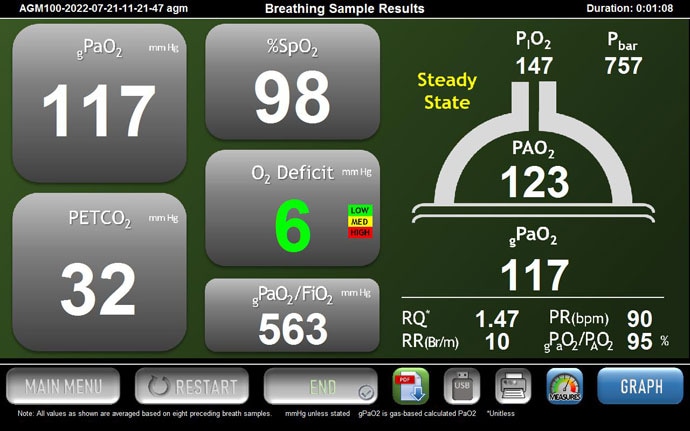

MediPines AGM100 display. Source: William C. McGuire, MD, MPH

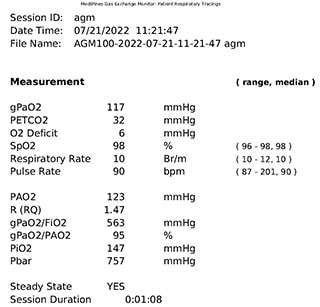

The machine gathers quite a bit of data, and the ultimate value that we were interested in was this concept of the oxygen deficit. The oxygen deficit is a surrogate for the alveolar to arterial oxygen difference, AaDO2, or what we more commonly refer to as the A-a gradient.

MediPines AGM printed results. Source: William C. McGuire, MD, MPH

Many of us learned in medical school, from Dr West's textbooks, that there's a normal A-a gradient and it increases with age. When someone is hypoxic or hypoxemic, there are five major causes, three of which manifest with an elevated A-a gradient.

We essentially correlate the A-a gradient to the oxygen deficit — it's been done multiple times prior to my study to validate this device — and we used the oxygen deficit essentially as a variable to predict the need for hospitalization and/or supplemental oxygen administration during hospitalization.

The way the AGM performs its function is, on this screen, as a practitioner, you can watch a patient breathing in real time, and you can make sure that each breath is similar in both volume and flow. That's important because the AGM makes some assumptions that a patient is in a steady state of breathing. The red line here at the top is the expired oxygen, and the blue line at the bottom is the expired carbon dioxide.

The top red line represents the level of expired oxygen. Source: William C. McGuire, MD, MPH

You can see that the values change during inspiration and expiration, respectively. You would expect the CO2 value to go up as the patient is expiring and the O2 value to go down and vice versa on inspiration. This is, essentially, a quality-control check that I would use as the practitioner. The real benefit of the AGM is in its output or its display. Unfortunately, because I stopped breathing, the display went away, but I can show you the general characteristics of the AGM here, nevertheless.

It gives you an atmospheric pressure and an inspired pressure of oxygen, and then it shows you the alveolar tension of oxygen, essentially in that semi-circle, which is supposed to represent an alveolus. It then uses the end-title CO2, which it measures down here, at 32 [Editor's note: The value was 31 in the video.]. I was hyperventilating a little bit.

It does some fancy math to, essentially, extrapolate what the arterial oxygen is by using the pulse oximeter, as well as a couple of fancy equations — Hill's equation and then a Severinghaus correction. That is what gives you a PaO2, which is displayed as gPaO2 because it's not an actual arterial O2. It's a generated value. The difference between the arterial and alveolar oxygen, the PAO2 and the gPaO2, is the oxygen deficit.

Glatter: In terms of using this value, I would assume that serial measurements are useful in assessing patients when they initially present, and then maybe if they start to have increased work or breathing or they decompensate. Other than your clinical skills (looking at work of breathing, accessory muscle use, and so forth), if someone's still saturating at 90% and you'd like to know, would this device be more predictive for the need for increase in oxygen requirement and the need for admission? Are your studies looking at these variables?

McGuire: Absolutely. I presented the study at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2022 conference along with many of my excellent colleagues — the manuscript is in process now — and it looked specifically at using a single value of the oxygen deficit at one point in time as a triage tool, and its discriminative ability to predict the need for hospitalization and the need for supplemental oxygen at any point during that hospitalization.

Poster presented at ATS 2022. Source: William C. McGuire, MD, MPH Download PDF

Most patients were enrolled within 24 hours of presenting to the emergency department, although many of them were enrolled within a few hours of arrival. They had dyspnea, and probably 70% of them were still on room air. A number had been placed on a small amount of oxygen for comfort. All measurements were obtained on room air, so I actually took patients off and allowed them to breathe quietly at room air for at least 5-10 minutes to ensure that there was no residual increased oxygen tension in the alveoli.

Now, what you asked about is much more interesting: How are serial measurements over time informative? Our institutional review board was written such that we are able to do that. In the multiple surges of COVID-19 that we have gone through in this country, with overwhelmed ERs, where patients are spilling out into tents on the parking lot and oxygen resources are sometimes scarce, we really wanted to look for a single-point discriminative tool that could help our ER colleagues decide potentially if someone is safe for discharge or maybe needs a little closer monitoring or even admission.

Glatter: In terms of sensitivity and specificity, do you have any values that reflect that in terms of an overall snapshot or from the study itself?

McGuire: Yes. We generated receiver operating characteristic curves for both admission to the hospital and the need for supplemental oxygen. The value for the area under the curve for hospital admission is a little over 0.7, which is very good. It's not the best in the world, but still quite valuable.

Those data were somewhat skewed by the fact that three or four patients who presented with COVID-19 had many other medical comorbidities and their primary care team wanted to admit them for observation purposes.

The real utility, at least in our study thus far, is in the need for supplemental oxygen. If someone had an oxygen deficit of 40 or above — and the oxygen deficit tracks with the A-a gradient but is a little bit larger than the A-a gradient — an oxygen deficit of 40 may represent an A-a gradient of 32 to 35, which is still quite high. An oxygen deficit of 40 or above predicted a need for supplemental oxygen at some point during that hospital course with, essentially, 99% accuracy. The area under the curve of the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.99.

Glatter: That's quite accurate. Dr West, arterial punctures are the way that I was trained. I never had the technology that now exists. We did serial arterial blood gases to look at patients' oxygenation and their ventilatory status. This is a big advance. What are your thoughts?

West: I agree with you. I was unfortunate in the sense that I'm terribly old, and I can remember when the earliest measurements were made. Richard Riley at Johns Hopkins, and a number of younger people whom I knew very well, developed the arterial puncture technique. He was the first person to measure the PO2 in blood using a bubble technique, which is now no longer used because the electrodes, of course, were a very valuable invention and I use it now. I can remember, when I was a younger clinician, I measured the alveolar arterial oxygen difference, the A-a gradient, on many patients, and it was, of course, a valuable indicator of their status.

Now, we can do essentially the same thing noninvasively, in a short period of time. I think it's a tremendous advance. I can remember it right from the beginning, way back in 1950 or so, when I first got into pulmonary medicine.

Glatter: Obviously, silent hypoxemia or occult hypoxemia is a real issue, especially in patients with COVID-19. This is applicable with that patient population but also in other patients, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and other types of lung pathology.

I wanted to also get into the question of whether this device could have a role in looking for patients with pulmonary embolism, cor pulmonale, right heart failure, or other things that are not COVID-19–related. Is there a use for your device in this capacity?

West: There probably is, although with COVID-19 around, that's center stage. No question about that. What is particularly being investigated at the present time is the efficiency of pulmonary gas exchange, which is destroyed by COVID-19. That's where most of the work is going.

You mentioned, for example, pulmonary embolism (PE), and there are many people thinking about that. PE will affect particularly the PCO2. By looking at the difference between the arterial value and the expired value, there may be information there that, as far as I know, has not been looked at yet, but it certainly will be.

I like to think of this as an all-encompassing way of looking at the overall gas exchange of the lung, where you're looking both at the gas side and the blood side at the same time and comparing them. There's good stuff there that hasn't yet been unearthed, in my opinion.

Glatter: Dr McGuire, I understand that there is some research that has been done on PE. I'm aware of a poster from your institution, but I'm not sure if you directly participated in the research. Can you comment on that?

Poster presented at ATS 2021. Source: Dylan Sieck, PhD Download PDF

McGuire: I did not participate directly in that study but I am familiar with it. The primary author shared his poster with me and it was an excellent study. There's quite a bit of untapped use here, not only in PE. I think there are several uses, as you alluded to, with COPD, cor pulmonale, and IPF patients being other great options.

Within the PE realm specifically, I think the mechanisms that underlie hypoxemia and hypoxia in PE are very unclear at times and multifactorial. As Dr West mentioned, CO2 is probably of greater importance. We still don't have an excellent way of noninvasively assessing arterial carbon dioxide content.

As Dr West mentioned, if you have an abrupt change in your alveolar CO2 tension and the circumstances seem appropriate for PE, it would still be a useful tool for trying to diagnose PE, even if the oxygen deficit is not as impaired. If there is a significant change in the carbon dioxide tension, that could be thought-provoking.

Glatter: I want to also discuss the issue of skin type and skin color, and how measurements of oxygen deficit may be more accurate than SpO2. Are you aware of any studies or ongoing research that are looking at oxygen deficit as a surrogate marker instead of relying on SpO2 in darker skin types and certainly in racial and ethnic diversity?

McGuire: This is a great question and thank you for asking it. It's one of the things that I am most interested in and passionate about studying prospectively moving forward. There is a group in Boston that is using the AGM in Uganda, but it is more as a point-of-care triage tool. They're not comparing it across different racial groups, as far as I'm aware.

I think that the oxygen deficit provides quite a bit of additional information, for two major reasons. One is that we rely on a pulse oximeter just as every other hospital or medical device does. There are excellent data from Sjoding's group in Michigan, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, and then a study from a different group, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, showing that pulse oximetry in isolation overestimates the arterial oxygen content in patients with darker skin tone — both Hispanic and African Americans — quite frequently.

We would be hamstrung by the same issues if we relied on our pulse oximetry alone, but because we have the alveolar oxygen tension, we get an extra bit of insight. What I have said multiple times to some of the trainees that I work with and my primary research mentor is that if you have an elevated oxygen deficit in a patient with darker skin tone, that deficit may actually be underestimating the severity of the deficit. If the pulse oximeter is overestimating the PaO2 but the PAO2 is low enough that the oxygen deficit is elevated, then the oxygen deficit may be more elevated than we're seeing.

Using this prospectively to look at the differences among a Caucasian patient, an African American patient, and maybe a patient with skin pigmentation somewhere in the middle would be a beneficial tool because of the rapidity with which you can get a measurement from this device. It would be a great way to think about how to triage patients who we often have neglected unintentionally due to the limitations of our technology.

Glatter: Dr West, I wanted to get your thoughts on this too, about addressing a huge problem with skin type and skin color and racial and ethnic diversity, because the literature has exploded in the past several years. The FDA is aware of the issues ongoing with pulse oximetry, yet they haven't formally made inroads to address the problems that exist with current near-infrared technology that pulse oximetry is based upon, from the early '70s.

Do you foresee that your device will, in some way, supplant the need for standard pulse oximetry going forward in the next several decades?

West: My guess is that you wouldn't supplant the need for pulse oximetry because it is such a simple, powerful way of measuring arterial oxygen saturation. I agree with you that there's a tremendous opportunity here to clarify what happens, for example, as skin color changes. I would just say that I think the potential is there and it hasn't yet been thoroughly mined.

Glatter: Well, that's good to hear because we know that pigment plays a role in terms of the pulse oximeter, and not only oxyhemoglobin, in terms of the LED and the infrared absorption. That's very important.

I want to wrap up. Would each of you provide one or two pearls or takeaways from our discussion? Dr West, I'll start with you.

West: I'm particularly interested in further development of the AGM. I personally think it has a tremendous future because it is very simple to use. It is very simple for the patient. There's no arterial puncture. I can remember vividly our problems with arterial puncture during my period as a physician.

It has the advantage of looking both at the blood side and the gas side, and there are not many investigations that do that.

It's going to be up to people like Cameron to do that. I'm jealous of the opportunities. I wish I was as young as Cameron, as I was a long time ago. I'm sure it will be extremely interesting to follow this up.

Glatter: Absolutely. Dr McGuire?

McGuire: Well, I just have to say thank you, Dr West. I grew up reading your textbook. The fact that I've had any success to this point is because I get to stand on the shoulders of giants such as yourself.

One takeaway point is that this device — or devices like it, if there are others in development that I'm unaware of — have already been well validated in the outpatient setting. We have now validated it in the inpatient setting for those who are rapidly changing with active parenchymal lung disease. That's really a beneficial thing moving forward. We've alluded to several untapped areas of research.

The use of this device to help triage or to help with patient decision-making could be applied in a number of different arenas, including discharge planning, need for oxygen supplementation at home, pre- and post-therapy — how someone's parenchymal disease improves or changes or how someone's pulmonary vascular disease improves or changes after the implementation of therapy.

There's a wide swath of research to be done, and I'm super-excited to be at the cutting edge and to be able to have access to something like this to help with decision-making.

Glatter: As you alluded to, length of stay and throughput are important metrics that we're looking at. This device certainly holds the opportunity to address that.

I want to thank both of you for your time. This has been very informative. I think our audience will truly appreciate the value of discussing such an important topic. Thank you.

Robert D. Glatter, MD, is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is an editorial advisor and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes.

John B. West, MD PhD, is emeritus professor of medicine and physiology, UC San Diego School of Medicine in La Jolla, California. His book, Respiratory Physiology: The Essentials, has been translated into 15 languages and is used around the world. West is one of the world's most noted physiologists for his work in respiratory physiology. His impressive body of research examines the lung in extreme environments, from high altitude atop Mt Everest to microgravity aboard the Space Shuttle and International Space Station.

W. Cameron McGuire, MD, MPH, is a pulmonary critical care physician and clinical instructor at UC San Diego School of Medicine in La Jolla, California.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape Emergency Medicine © 2022 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Robert D. Glatter, John B. West, William C. McGuire. Novel Respiratory Gas Exchange Meter for Triaging Patients - Medscape - Aug 16, 2022.

Comments